Thai Food: When Food Becomes a Language of Everyday Life

- Understanding Thai Cuisine: Core Flavor Logic and Ingredients

- Street Food Culture in Thailand

- Regional Thai Cuisine: When Each Region Tells a Different Story

- Must-Try Thai Dishes

- Night Markets and Food Courts in Thailand’s Everyday Eating Culture

- Vegetarian, Vegan, Halal Options and Food Allergy Considerations

- Food Safety, Health & Practical Tips

- Culinary Experiences Beyond Eating

- Practical Costs & Food Budgeting

- Visual & Social Media Considerations

In Thailand, food is inseparable from daily life. It appears in ordinary moments, a quick breakfast from a street cart, a simple lunch at a roadside stall, or an evening meal at a neighborhood market. For travelers, understanding Thai food is one of the most direct ways to connect with local rhythms and ways of living.

Thai cuisine is accessible yet far from simple. A single meal often reflects layers of experience, regional habits, and long-standing cooking practices. Across regions, food tells different stories, from the bold flavors of the South and the rustic character of Isan to the balanced elegance of Central Thailand.

This guide explores Thai food beyond what to eat, focusing instead on how, where, and why people eat the way they do, offering a grounded starting point for understanding Thai cuisine through everyday life.

A snapshot of everyday Thai comfort food (Source: Instagram — @law14)

Understanding Thai Cuisine: Core Flavor Logic and Ingredients

Eating well in Thailand does not require memorizing dozens of dish names. What matters more is understanding the logic behind how Thai food is cooked and seasoned. Rather than relying on rigid recipes, Thai cuisine is shaped by a delicate balance of flavors, the use of fresh ingredients, and eating habits refined through generations.

The Five Flavor Pillars of Thai Cuisine

Most Thai dishes are built around five core flavor groups. What sets Thai cuisine apart is that these flavors are rarely separated; instead, they appear together within a single dish, carefully balanced rather than layered one by one.

- Sweet – gentle rather than sugary, typically drawn from palm sugar or cane sugar.

- Sour – most often from fresh lime or tamarind, bringing brightness and cutting through richness.

- Salty – not limited to salt, but developed through fish sauce, dried shrimp paste, and fermented seasonings.

- Spicy – from fresh chilies, dried chilies, or chili pastes, ranging from mild to intensely hot depending on the region.

- Umami – a deep savoriness created by fermented ingredients, slow-simmered broths, or dried seafood.

For Thai people, this balance of flavors is learned early and absorbed naturally, shaped by shared meals at home and the everyday practice of adjusting taste at the table rather than following fixed recipes.

Ingredients Found Everywhere

Thai cuisine relies on familiar ingredients, yet it is their combination and treatment that create a distinctive character.

- Fish sauce forms the backbone of both saltiness and umami, appearing across stir-fries, soups, and salads.

- Chilies are used not only for heat, but also for aroma and color.

- Lime is almost always freshly squeezed at the table, with bottled juice rarely used.

- Herbs such as lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves, galangal, and Thai basil lift dishes with fragrance without weighing them down.

- Palm sugar provides a rounded, depth-filled sweetness, distinct from refined sugar.

What these ingredients share is an emphasis on freshness. Rather than relying on frozen storage, Thai cooking prioritizes ingredients prepared and consumed within the day - a principle especially evident in street food culture.

Rice and the Culture of Thai Meals

Rice is not simply a side dish in Thailand; it sits at the center of the meal. Depending on the region, different types of rice shape how food is eaten and shared.

- Jasmine rice is most common in Central and Southern Thailand, valued for its soft texture and gentle fragrance.

- Sticky rice plays a central role in the North and Northeast, often eaten by hand and paired with savory dishes.

Beyond nourishment, rice helps balance strong flavors, softening heat and saltiness and making meals feel more approachable, especially for those unaccustomed to bold seasoning.

Spiciness in Thai Cuisine

Spice is a defining feature of Thai food, but not all dishes carry the same level of heat. Some are barely spicy, others offer just enough heat to awaken the palate, while a few are intense enough that even locals approach them with caution.

What matters is that spiciness is adjustable. In everyday dining, it is entirely normal to express personal preference when ordering, reflecting a food culture that values balance and comfort over strict rules.

Street Food Culture in Thailand

Street food is a symbol of Thai identity and a social, communal experience rather than just a quick meal. It represents a "living, breathing food culture" passed down through generations.

For travelers, stepping into the world of street food is also a step into the rhythms of everyday Thailand, where meals are shaped by habit, proximity, and shared space rather than formality.

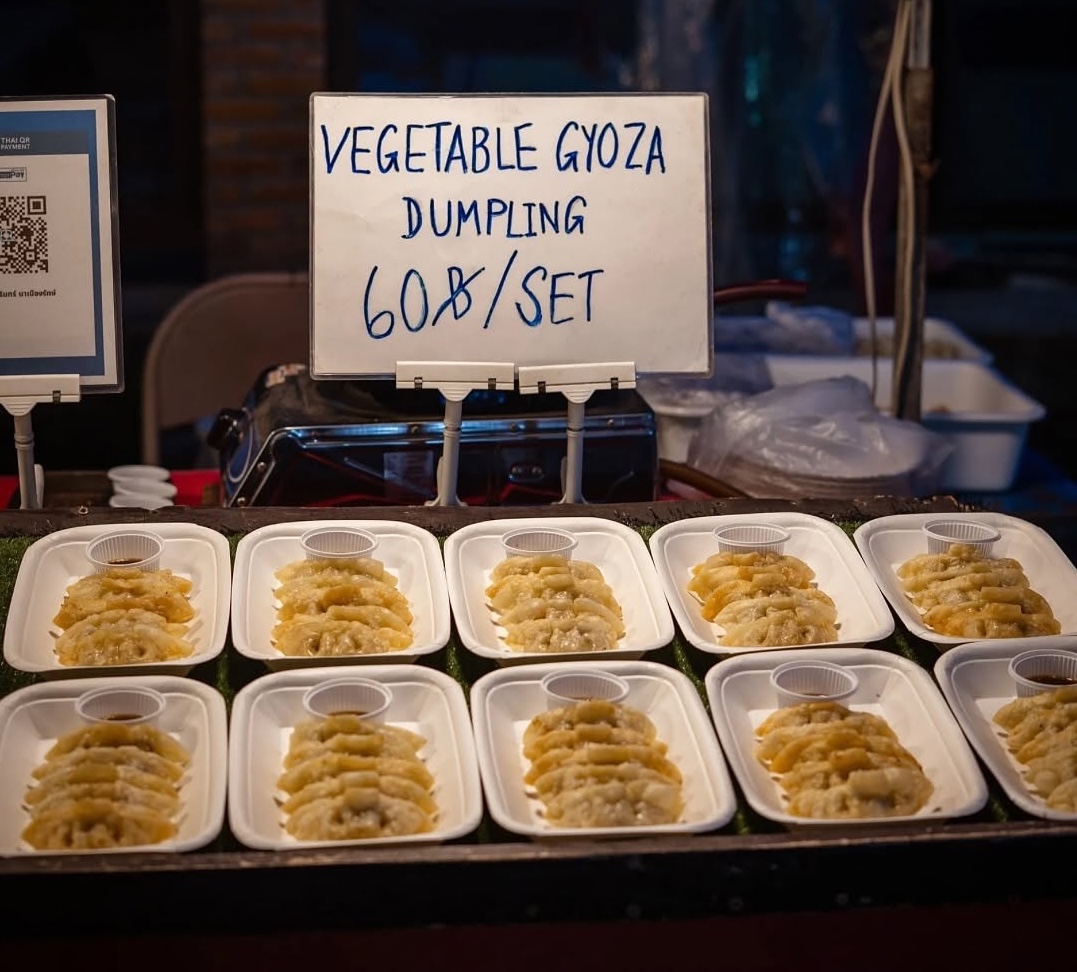

Vegetable gyoza dumplings at a night market stall, ready to serve. (Source: Instagram — @bangkok.explore)

What Street Food Really Means in Thailand

In Thailand, a food stall may be nothing more than a pushcart, a few low plastic stools, a small gas burner, and a pot of broth sending up steam. Behind this simplicity, however, lies skill refined over years. Many vendors focus on a single dish, cooking it day after day, adjusting small details until consistency becomes second nature.

Street food, therefore, is not about eating casually or temporarily. For locals, it is a proper meal, a familiar meeting point, and a habit woven into everyday routines.

Eating by the Clock: From Early Morning to Late Night

Thai street food follows distinct rhythms throughout the day. Morning brings sticky rice, porridge, and noodle soups — quick, practical meals that start the day. Midday sees rice stalls, stir-fried noodles, and ready-made dishes catering to office workers and passersby. Evenings and nights belong to night markets and roadside stalls that stay open late, when the atmosphere is at its liveliest.

In large cities such as Bangkok, finding food at midnight is entirely normal. In Chiang Mai, street food is more closely tied to evening markets and a slower pace, shaped as much by experience as by appetite.

A colorful Thai street food stall, with fresh ingredients neatly displayed and vendors preparing dishes to order. (Source: Markus Winkler via Unplash)

Hygiene and Food Safety

One of the most common concerns among travelers is the safety of street food. In practice, locals follow a set of simple, practical cues when choosing where to eat.

Stalls with a steady flow of local customers, especially office workers, are generally trusted. Ingredients are cooked continuously rather than left sitting for long periods, and cooking areas tend to be compact and well managed, with utensils regularly rinsed during service.

Thai street food favors a rhythm of cooking fast, selling fast, and eating immediately. This approach minimizes long-term storage and helps explain why many small stalls maintain loyal customers for years.

The Social Experience on the Pavement

Eating street food is about more than the meal itself. It is the act of waiting beside a hot stove, listening to the sounds of cooking, and watching vendors work with practiced ease. It is sharing a narrow space with strangers, exchanging brief smiles or gestures over plastic stools.

For many travelers, the most memorable meal in Thailand is not found in a fine dining room, but in the simple moment of holding a hot bowl of noodles, sitting low to the ground, and observing the steady flow of life under the warm glow of street lights.

Regional Thai Cuisine: When Each Region Tells a Different Story

Referring to “Thai food” as a single, unified concept is only a starting point. In reality, Thai cuisine is shaped by regions that differ widely in climate, history, and ways of life. Each region carries its own dominant tastes, cooking approaches, and food philosophy, all closely tied to the daily lives of its people. Understanding regional cuisine is therefore a way of understanding Thailand itself, beyond the familiar dishes often found on tourist menus.

- Central Thailand: Balance and Refinement:

- Central Thailand is where many dishes now considered “classic” Thai cuisine first took shape. The flavors here are rounded and harmonious, avoiding extremes and appealing to a wide range of palates.

- Dishes from this region typically balance sweet, salty, sour, and spicy elements without allowing any single flavor to dominate. Cooking emphasizes finesse and thoughtful presentation, reflecting historical influences from royal and courtly kitchens. This is also why many dishes most familiar to international travelers originate from Central Thailand.

- In cities such as Bangkok, Central Thai food is found everywhere, from humble rice shops to family-run restaurants, making it the most approachable regional style for those new to Thai cuisine.

- Northern Thailand (Lanna): Rustic and Herb-Driven

- Northern Thai cuisine carries a slower, more grounded character shaped by mountains and forests. The flavors are generally less sweet and less spicy, leaning instead toward herbs and the natural taste of ingredients.

- Sticky rice sits at the heart of the meal, often eaten by hand and paired with savory accompaniments. Northern dishes tend to use less oil and lighter seasoning, yet achieve depth through the careful use of local herbs and spices.

- In Chiang Mai, Lanna food is most visible in neighborhood markets and family-run eateries. Meals here feel intimate and familiar, closer to home cooking than to formal dining.

- Northeastern Thailand (Isan): Bold and Uncompromising

- Isan cuisine is defined by intensity and directness. Strong sourness and heat, frequent use of fermented ingredients, and dishes served at room temperature reflect both the region’s working lifestyle and its harsher climate.

- Isan dishes are often simple in appearance but unapologetically bold in flavor. Nothing is softened or hidden, eating Isan food is about experiencing flavors as they are. This honesty is precisely why Isan cuisine is deeply loved by Thais and widely found in urban areas across the country.

- In major cities, Isan restaurants are often filled with local diners, especially in the evenings, where the atmosphere is lively, informal, and rooted in shared eating.

- Southern Thailand: Heat, Spice, and the Sea

- Southern Thailand is often regarded as the region with the most intense flavors. Dishes are deeply spicy, with heat that builds and lingers, driven by generous use of fresh chilies and pungent spices. Seafood plays a central role, reflecting the region’s coastal way of life.

- Southern cuisine shows strong influences from Malay and Indian cultures, particularly in its use of spices, herbs, and richly layered curries. While the food can be challenging for unaccustomed palates, it leaves a lasting impression on those familiar with Thai flavors.

- In coastal destinations such as Phuket, Southern dishes are part of everyday local meals and small neighborhood eateries, not confined to restaurants aimed at tourists.

Regional Cuisine as a Living System

Regional Thai cuisines do not exist in isolation. As people move, they bring the food and tastes of their home regions with them. Yet wherever these dishes appear, they continue to carry traces of their origins. For travelers, recognizing these regional differences not only leads to better meals, but also offers a deeper understanding of the cultural landscapes that shape life across Thailand.

Must-Try Thai Dishes

In daily life, Thai cuisine revolves around a small number of familiar dish categories. These dishes are generally simple in preparation, use widely available ingredients, and appear across public eating spaces. While they differ in flavor, cooking methods, and how they are eaten, they all share an emphasis on convenience and flexibility.

- Noodle Dishes

- Noodles are among the most common everyday meals in Thailand, particularly for breakfast and lunch. The base typically consists of rice noodles or egg noodles, paired with broth or sauce, slices of pork, chicken, beef, or seafood, and a small selection of vegetables.

- Depending on the dish, noodles may be served in a clear or lightly seasoned soup, tossed with sauce, or stir-fried over high heat. Broths are often simmered from bones and adjusted at the table with fish sauce, sugar, chili, and lime, allowing diners to fine-tune the balance themselves. Stir-fried versions are cooked quickly, usually with egg, bean sprouts, scallions, and pre-mixed sauces prepared in advance.

- Flavors range from mild and lightly savory to clearly sour and spicy. Noodle dishes are almost always eaten hot and are commonly found at street stalls, fresh markets, and small neighborhood shops throughout the day. Prices typically fall between 50 and 100 THB, while more region-specific noodle dishes, such as Northern-style Khao Soi, are usually priced slightly higher, around 60 to 120 THB, reflecting their richer ingredients and longer preparation.

- Rice-Based Meals

- Rice-based meals form the backbone of everyday eating, especially at lunch and dinner. These meals usually consist of plain steamed jasmine rice served with one or more savory toppings, such as stir-fried or braised meats, boiled pork or chicken, fried eggs, vegetables, and a simple dipping sauce.

- The focus is placed on the accompaniments rather than the rice itself. Meats are seasoned assertively so they can be eaten alongside neutral rice, while fried eggs and uncomplicated vegetable dishes appear frequently as balancing elements. Dishes like Pad Kra Pao exemplify this category: quick to prepare, strongly flavored, and designed to be eaten without ceremony.

- Rice meals are generally approachable and not excessively spicy by default. They are most commonly eaten in casual eateries, canteens, and food courts, where prices remain highly consistent nationwide, usually ranging from 50 to 80 THB. This affordability helps explain their role as everyday “default” meals for students, office workers, and families alike.

- Curry Dishes

- Thai curries are prepared using ground spice pastes combined with coconut milk, meat or seafood, and vegetables. Each curry reflects a distinct balance of chilies, herbs, and spices, resulting in noticeable differences in aroma and heat level across regions.

- Curries tend to have a rich, creamy texture, pronounced herbal fragrances, and a balance between spiciness and richness. They are typically served in smaller portions alongside plain rice, allowing diners to moderate the intensity of flavor with each bite.

- Compared to basic rice or noodle dishes, curries occupy a slightly higher position in everyday dining. They are commonly found in local eateries and family-run restaurants, where they are often cooked in advance and kept warm for service. Prices usually range from 150 to 300 THB, depending on the quality of ingredients and whether the curry paste is prepared in-house.

- Mixed Dishes and Salads

- Thai-style mixed dishes and salads emphasize freshness and contrast. Common ingredients include vegetables, shredded green papaya, seafood, and boiled or grilled meats, seasoned primarily with fish sauce, lime juice, chilies, and palm sugar.

- These dishes are mixed quickly and eaten immediately. Their flavor profile is distinctly sour, salty, and spicy, with little richness, making them especially refreshing in hot weather. They are often shared among several diners and eaten alongside rice or sticky rice rather than on their own.

- Such dishes are especially common in local markets and neighborhood eateries, particularly in Northern and Northeastern Thailand. Most variations of Som Tum and similar salads remain highly affordable, typically costing 40 to 70 THB, reinforcing their role as casual, everyday food rather than formal dishes.

Pad Thai with shrimp, fresh off a floating market boat (Source: Instagram —@jenn.eats)

- Snacks and Sweet Dishes

- Thai sweets and snacks rely heavily on coconut milk, sticky rice, fresh fruit, and sugar. Textures tend to be soft and comforting, with sweetness kept moderate and dairy products rarely used.

- These items are usually eaten at room temperature or chilled and are sold in small portions at markets and street stalls. They are commonly consumed between meals or as a light finish after eating. Prices generally range from 60 to 150 THB, depending on ingredients and presentation.

- Many desserts are seasonal, closely tied to the availability of fresh fruit throughout the year. Dishes such as mango sticky rice become particularly prominent during peak fruit seasons, reflecting the strong connection between Thai sweets and agricultural cycles.

Fresh mango sticky rice, finished with coconut cream. (Source: Instagram —@jenn.eats)

Night Markets and Food Courts in Thailand’s Everyday Eating Culture

Night markets and food courts are two common dining spaces that coexist in Thailand’s urban life. Although they differ in form and operation, both focus on familiar dishes that are quick to prepare, consistently priced, and easy to access. These spaces bring together a wide range of everyday foods within a single setting.

Night Markets

Night markets typically begin operating in the late afternoon and continue late into the night. Food stalls line the walkways, with each vendor usually specializing in one or a small number of dishes. Common offerings include stir-fried noodles, rice dishes, grilled foods, salads, sweets, and various snacks.

Cooking at night markets is largely done on-site. Ingredients are partially prepared in advance and finished to order. Food is usually served hot and eaten immediately, rather than taken away for long periods. Seating is informal and flexible, ranging from low tables and plastic stools to standing areas.

In large cities such as Bangkok, night markets are often located in residential neighborhoods and tourist areas. In Chiang Mai, they are closely tied to evening walking streets and local community markets. Each market tends to have a stable lineup of familiar vendors, with little change over time.

Food Courts in Shopping Malls

Food courts are centralized dining areas located inside shopping malls or office buildings. Stalls are permanently arranged and offer common dishes such as rice meals, noodles, curries, soups, salads, and desserts.

Food in food courts is prepared according to standardized processes. Dishes are cooked quickly, portion sizes are consistent, and flavors tend to vary little between servings. Dining areas provide fixed seating, air conditioning, and shared hand-washing facilities.

Food courts are widespread in major shopping centers in Bangkok as well as in tourist cities like Phuket. They serve as a familiar and practical dining option for office workers, families, and groups of friends, especially during lunch and dinner hours.

Prices at night markets and food courts are generally predictable and remain within a comfortable range. At local night markets, most main dishes fall between 40–80 THB, while food courts inside shopping malls tend to be slightly higher, usually around 50–100 THB. Desserts and snacks are lighter on both the palate and the budget, often priced at 20–50 THB per serving.

For first-time visitors, food courts offer a sense of ease: clearly displayed prices, consistent portions, and air-conditioned seating make them straightforward and stress-free. Night markets, by contrast, invite a slower pace. They are better suited to lingering, trying several small dishes, and taking in the atmosphere of local evening life as it naturally unfolds.

Vegetarian, Vegan, Halal Options and Food Allergy Considerations

Thai cuisine is highly flexible and allows for a wide range of adjustments to suit different dietary needs. However, due to the traditional use of seasonings and ingredients, certain dietary preferences require clear understanding to avoid confusion when choosing dishes.

Vegetarian and Vegan Eating

Vegetarian and vegan food exists within Thai food culture, but these concepts do not always align with common Western definitions. Many dishes that do not contain visible meat may still include animal-derived ingredients.

Common ingredients that often cause confusion include:

- Fish sauce

- Shrimp paste or fermented fish products

- Bone-based broths

- Oyster sauce

Thai-style vegetarian dishes typically rely on tofu, mushrooms, vegetables, and aromatic seasonings, but attention must be paid to the sauces and seasonings used. In a local context, vegetarian eating is often associated with religious practices or specific occasions rather than a daily lifestyle choice.

Halal Food

Halal food is clearly present in areas with Muslim communities and in major cities. Halal dishes follow specific rules regarding ingredients and preparation, avoiding pork and alcohol.

Halal cuisine in Thailand commonly includes:

- Rice and noodle dishes with chicken or beef

- Curries prepared without cooking alcohol

- Grilled and stewed dishes

Halal eateries usually display clear signage and operate separate cooking areas. In large food courts and night markets, halal stalls are typically separated to prevent cross-contamination.

In terms of cost, halal dishes in Thailand are generally priced similarly to regular meals, typically ranging from 50–100 THB for rice or noodle dishes. For visitors, choosing eateries with clear halal signage helps avoid confusion over ingredients, especially in busy markets with many food stalls.

Food Allergies

Thai cuisine uses many ingredients that can trigger food allergies. Some of these components appear frequently across different dishes and may not be immediately visible.

Common allergens include:

- Peanuts

- Seafood and fermented fish products

- Eggs

- Dairy and coconut milk

Because many dishes are pre-seasoned, completely removing certain ingredients is not always possible. Small street stalls often follow fixed recipes, while larger restaurants and food courts generally offer greater flexibility for customization.

Availability and Accessibility

Vegetarian, halal, and allergy-conscious options are not uncommon, but their availability varies by location and dining format. Night markets and small eateries tend to focus on traditional dishes, while shopping malls and tourist-oriented areas usually provide a broader range of dietary options.

Food Safety, Health & Practical Tips

Eating in Thailand takes place largely in a hot, humid climate and within a fast-paced food service culture. Most dishes are prepared for immediate consumption, but there are several differences in food preparation and handling worth noting, especially for visitors who are not yet accustomed to local climate conditions and seasoning practices.

Drinking Water and Ice

Tap water is not used directly for drinking. In everyday life, bottled water is the standard option and is widely available at convenience stores, food stalls, and markets.

Ice used in beverages is typically factory-produced and distributed in large bags. This ice is usually cylindrical or hollow in shape, clearly distinct from homemade ice. Hand-crushed ice made from tap water is rarely found in public dining spaces.

Freshly Cooked Food and Pre-Prepared Dishes

Common dishes such as noodles, rice meals, stir-fries, and curries are either cooked to order or kept hot for short periods. Core ingredients are pre-prepared, but the final cooking step usually happens just before serving.

Some rice and curry stalls display trays of pre-cooked food. These dishes are kept continuously heated and are generally sold out within the day. Overnight storage of cooked savory dishes is uncommon.

Salads, Mixed Dishes, and Cold Foods

Mixed dishes such as Som Tum or seafood salads are prepared and eaten immediately. Vegetables and fruit may be prepped in advance, but seasoning and mixing occur only after an order is placed.

Cold dishes do not form a central part of Thai cuisine. Aside from certain mixed salads, most foods are consumed hot or warm.

Raw and Lightly Cooked Foods

Thai cuisine does not commonly feature raw meat. However, certain regional dishes may include meat or seafood cooked to a light doneness, particularly fresh fish or seafood.

These dishes are usually found in specific local contexts and are not standard offerings at everyday food stalls. Most foods sold at night markets and food courts are fully cooked.

Spices, Heat Levels, and Adaptation

Many Thai dishes use fresh chilies, dried chilies, and strong seasonings. Spice levels are not fixed and vary by vendor. Some dishes are pre-seasoned, while others can be adjusted during preparation.

Pairing spicy dishes with plain rice or sticky rice is a common eating practice that helps soften the intensity of the flavors. In practice, many people find they adapt to spice levels after a few days, especially when choosing cooked dishes or those with broth.

Eating Rhythm and Portion Size

Dining in Thailand does not follow rigid meal schedules. Food stalls open and close according to local demand. Many people eat several smaller meals throughout the day rather than one large meal.

Portion sizes are generally modest, making it easy to sample multiple dishes in a single meal, particularly when eating communally.

Culinary Experiences Beyond Eating

Beyond eating at stalls, restaurants, or markets, Thai cuisine is also encountered through activities centered on learning, observation, and direct participation. These experiences focus less on the number of dishes consumed and more on cooking processes, ingredients, and the everyday contexts in which food is prepared and used.

Cooking Classes

Cooking classes are a common experience in tourist cities and areas popular with long-stay visitors. Class content usually focuses on foundational dishes such as stir-fried noodles, curries, hot-and-sour soups, and mixed salads.

A typical session includes:

- An introduction to key ingredients and seasonings

- Hands-on preparation of each dish

- Eating the food on-site after completion

Ingredients are prepared in advance, but participants take part in essential steps such as pounding spice pastes, seasoning, and adjusting flavors. These classes usually last half a day or a single morning.

Local Food Tours

Food tours emphasize moving between multiple eating spots within the same area. They often take place in the evening or early morning, depending on the type of food being explored. A food tour may include simple noodle or rice stalls, local mixed dishes or regional specialties, and a stop for sweets or small snacks.

The experience centers on observing cooking techniques, learning how to order, and eating on the spot rather than consuming large quantities. Routes are usually fixed and feature long-established stalls with consistent operations.

Tom Yum soup with fresh herbs, bold and comforting. (Source: Undo Kim via Pexel)

Traditional and Fresh Markets

Traditional markets are where raw ingredients come together: vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, herbs, spices, and prepared foods. These markets typically operate in the morning. Visitors can observe how ingredients are sorted and stored, seasonal herbs and fresh spices, pre-prepared components used for home cooking. Markets function not only as commercial spaces but also as everyday community environments where meals begin at the level of raw ingredients.

Fresh seafood skewers on ice, ready for the grill at a lively street stall (Source: Instagram — @annakarlaenriquez)

Region-Specific Food Experiences

Some culinary experiences are closely tied to specific regions and everyday eating habits. In the North, meals are often built around sticky rice and shared dishes eaten in a family-style setting. In the Northeast, grilled foods and boldly seasoned mixed dishes dominate the table, while in coastal areas, daily meals revolve around freshly sourced seafood. These experiences tend to be informal and small in scale, shaped by local routines and availability rather than created as staged or performative attractions.

Timing and Seasonality

Many food experiences depend on seasonal availability. Fruits, seafood, and certain desserts appear only at specific times of the year. This seasonality directly influences cooking class content, food tour itineraries, and the dishes offered in markets.

Practical Costs & Food Budgeting

Food costs in Thailand are generally affordable and predictable, especially when you eat the way locals do. Most everyday meals take place at street stalls, markets, or food courts, with prices that work well for both residents and visitors.

A typical rice or noodle dish usually costs around 40–80 THB at night markets and small local eateries. In shopping mall food courts, prices are slightly higher, averaging 50–100 THB for a main dish. Desserts and snacks are cheaper, commonly ranging from 20–50 THB per portion.

Because portions are modest and choices are plentiful, many people prefer eating several small meals throughout the day rather than one large one. This approach keeps spending manageable while making it easier to sample a wider range of dishes without feeling overwhelmed.

Visual & Social Media Considerations

Thai food is naturally easy to capture, especially in everyday settings. Open kitchens, food cooked right in front of you, and the bright colors of fresh ingredients create good moments without much effort. Night markets and busy street stalls often offer the most interesting scenes simply because everything is happening at once, with no need to stage or set anything up.

When filming or taking photos at markets, it helps to stay aware of the space around you. Most stalls are small and work quickly, so keeping things brief, staying out of walkways, and not slowing the vendor down makes a big difference. In many cases, a quick look or short question before filming up close is enough to keep things comfortable.

Food content in Thailand usually feels strongest when it’s about noticing and recording what’s already there, rather than trying to turn a meal into a performance. Moments that show how people actually eat, cook, and interact tend to feel more genuine and they’re often the ones that stay with you the longest.

Thai cuisine is not defined by elaborate dishes or showy presentation, but by its place in everyday life, from roadside rice stalls and bowls of hot noodles in the morning to crowded night markets after work. Its flexibility, familiar ingredients, and the ease with which dishes can be adjusted to personal taste make Thai food approachable without ever being simplistic. When the eating context, local habits, and the role of food in daily routines are understood, the culinary experience in Thailand becomes more intuitive, more grounded, and far more meaningful than simply “trying local food.”